by Alan Briskin | Collective Folly, Collective Wisdom, Conscious Capitalism, Leadership, Politics

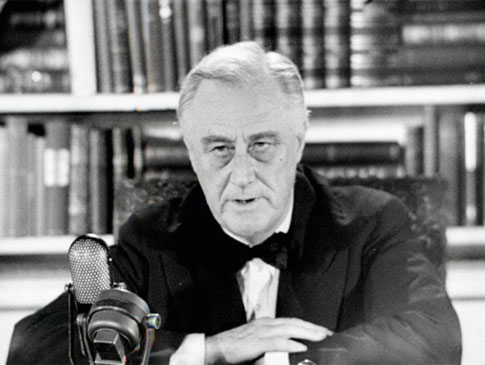

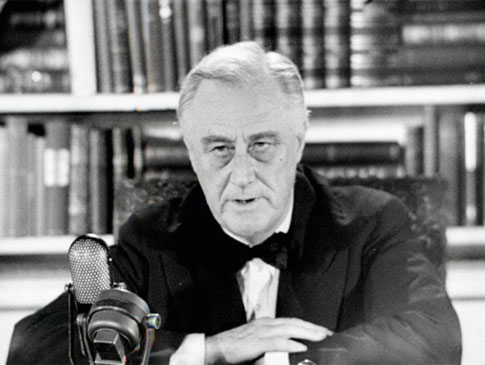

There are consequences to avoiding our fate, especially at the collective level and especially when we have been given stark warning. In this case, the warning came from Franklin D. Roosevelt and it is as much about the interior domain of the collective as well how it manifests at the highest corporate and government levels. Clothed by interest groups shaped by fear and greed, the ensuing garment hides self-interest while emphasizing the fine fit of those who have prospered. The warning Franklin delivers is about ignoring our social responsibility at the same time we scapegoat those who have not succeeded. The consequence is a putrefaction of our thought process, a shrillness to our emotional responses, and a fatalism about a better future.

From Becoming Conscious of Capitalism:

The economic bill of rights highlighted a scar in the American psyche. Roosevelt’s time in office, which included a failed coup d’état directed against him, deepened the resolve of factions opposed to government intervention. From this moment on, a widening split would cleave those who believed in federal intervention from those who perceived arrogance in a government that addressed questions of economic distribution.

Read more…

Filmed presentation of FDR’s speech on an Economic Bill of Rights:

by Alan Briskin | Collective Folly, Conscious Capitalism, Politics

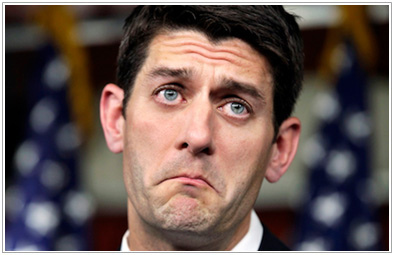

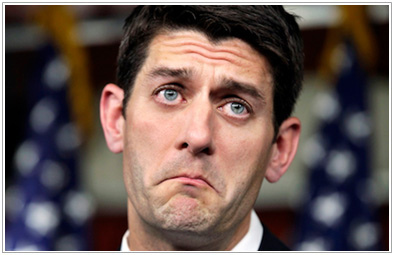

As if on cue, Republican Party nominee for Vice President and current congressman, Paul Ryan, was back in the news warning about “generations of men not even thinking about working or learning to value the culture of work, so there is a real culture problem here that has to be dealt with.”

As if on cue, Republican Party nominee for Vice President and current congressman, Paul Ryan, was back in the news warning about “generations of men not even thinking about working or learning to value the culture of work, so there is a real culture problem here that has to be dealt with.”

Ryan then offers a bait and switch, condemning government programs that have historically addressed the consequences of poverty and offering up free market solutions, like limiting long-term unemployment insurance and opposing living wage policies. Somehow his fear of a “dependency culture” has led him to believe in the superior intelligence of private enterprise and the character faults of an underclass bred to depend on government assistance. How I would love to agree with him, but then we would both be horribly wrong.

For some historical antecedents to this debate, read my two-part series from “Becoming Conscious of Capitalism”, beginning with How Wealth Became Concentrated and the Poor Were to Blame: Paupers are Everywhere.

by Alan Briskin | Collective Wisdom, Community, Conscious Capitalism, Photography

I AM NOT DONE…. I SHALL PERSIST…. I SHALL RETURN

~ Alan Briskin

Talmudic Commentary: “Pshh, Big shot. I’ll believe it when I see it.”

Dear Friends and Subscribers to Becoming Conscious of Capitalism,

When I first began writing, I sought to discover new perspectives about our social and economic arrangements called capitalism.

I wrote at the beginning:

“At a time when many voices are calling for a new form of conscious capitalism, this is a chance to step back and consider where we have been and how we can best shape the future.”

My intent then, as it is now, was to share my journey of exploration, to clarify, provoke, inform, and at times delight.

Read More

by Alan Briskin | Collective Folly, Conscious Capitalism, Politics

Becoming Conscious of Capitalism:

The Death and Rebirth of Prosperity’s Dream

a serial narrative by Alan Briskin

FREE: SUBSCRIBE NOW

FREE: SUBSCRIBE NOW

to receive your weekly dose of reality

(Watch for the next series)

Postmark, Oakland, CA, August 11, 2012

Today the Republican nominee for President Mitt Romney chose the Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan to be his vice presidential nominee. The news was filled with many different perspectives about this selection, one of which was the unusual philosophical connection Ryan has with the author Ayn Rand.

Below is an excerpt about Ayn Rand from my new serial narrative, Becoming Conscious of Capitalism, and her unusual link with Paul Ryan.

I wrote the serial over the past few months with an eye to collective folly but also as a serious attempt to discover the links between capitalism and partisan politics. Along with my commentary, I include some of my HDR (high dynamic range) photography as well as FLASH POINTS ripped from today’s headlines and those of earlier historic perspectives.

I hope you will find the serial stimulating, an irreverent romp through history as we polka our way to the Presidential elections. Sometimes trying to keep sane means embracing insanity as an important herald of what to pay attention to. Read on for a “sneak preview” excerpt from Chapter Six of the series…

Read More

by Alan Briskin | Conscious Capitalism

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter One:

Eight-Leaved Clovers of the World, Unite

London, 1847

n a bleak November day, two men trudged along Great Windmill Street in London. They breathed in air yellow from industrial waste and pondered the extremes of wealth and poverty that had sprung up like gods and demons across the city landscape. Between their poor vision and the London fog, they could barely see a foot ahead of themselves, but in their minds’ eye, they saw a future of increasing economic division. Somewhere not too distant in time, they believed, anger would well up among the workers, culminating in revolutionary action.

n a bleak November day, two men trudged along Great Windmill Street in London. They breathed in air yellow from industrial waste and pondered the extremes of wealth and poverty that had sprung up like gods and demons across the city landscape. Between their poor vision and the London fog, they could barely see a foot ahead of themselves, but in their minds’ eye, they saw a future of increasing economic division. Somewhere not too distant in time, they believed, anger would well up among the workers, culminating in revolutionary action.

One of them wanted to show the world with a simple parable, like an ancient prophet, why society’s self-destruction was inevitable. The other, the son of a Jewish family that adopted Christianity, was someone born into affluence and respectability, but called to forsake his relations, though not so much that he wasn’t willing to borrow money from them. So it was that these two compatriots, Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, made their way to the Red Lion Pub.

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

FLASH POINT

New York City, 1890

“These are the economic conditions that enable my manufacturing friend to boast that New York can “beat the world” on cheap clothing. In support of his claim he told me that a single Bowery firm last year sold fifteen thousand suits at $1.95 that averaged in cost $1.12 ½.”

~ From How the Other Half Lives, written by Jacob Riis

It was as if the two of them were destined to emerge victorious among a ragtag group of immigrants, intellectuals, utopians, anarchists, and protesters who had come together to chart a new social contract. Marx, full of himself, was never more alive than in a good intellectual battle, and Engels had the cheerfulness, adaptability, and good nature of a born organizer. “This time we will have our way,” he wrote to Marx before they arrived in London. And have their way, they did. The German Workers’ Educational Union, a convenient public relations front for the Communist League, voted to adopt their draft of the Communist Manifesto, which Marx had read portions of out loud to the group. However, what the group heard was in some doubt, given Marx’s accent and lisp. One witness recalled that when Marx said “workers,” some thought he said “eight-leaved clovers,” which must have been somewhat confusing.

Marx and Engels were early practitioners of a particularly speculative and ambiguous field of social science initially described as “political economy” and later shortened to “economics,” denoting a more neutral and quantitative perspective regarding society’s production and distribution of goods and services. Originally derived from an ancient Greek word, the root meaning of economics had to do with the management or administration of a household. But the household was now nations and transnational corporations.

Marx and Engels were visionaries, foreseeing a new economic institution that was still emerging, one that would harness the energies of human imagination in no less dramatic a fashion than Prometheus’s giving fire to humanity. Engels, in particular, was awed by what was occurring around them. He was not alone marveling at the extraordinary gifts of commerce, high culture, diversity, social mobility, new services, and hope that this new economic institution engendered. Capitalism was a dream for many of an ever-lasting prosperity. Marx and Engels sought to waken them to its true consequences.

In mid-19th-century London, the physical location where Marx and Engels delivered the Manifesto, their parable on social disintegration, there was no greater center of commerce in the world. It was a marketplace without comparison, a hive of activity where “at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs” could be found. Incomes were, on average, 40% higher there than in other English cities, and the results were palpable, with a level of escalating consumer demand driving entrepreneurial forces toward novelty, innovation, new technologies, and entire new industries.

These new economic arrangements were a thunderbolt challenging hundreds if not thousands of years of human history. Commerce of this proportion was a social retort to common beliefs about the inescapability of material deprivation for the masses. Capitalism was to be a buffering institution between the transcendent and random forces of God and nature on the one hand and control over one’s own personal destiny on the other. Trade of this form and intensity was a force for progress, freedom, and increasing liberty. What could go wrong?

The question hovers over us today as it did for Marx and Engels. They were witnesses to an emerging economic institution that still had no agreed-upon name. In the Communist Manifesto, they were more prone to talk about a bourgeoisie class than a capitalist class, but over the next 20 years, Marx would settle on words and terms like capitalist and capitalist mode of production, using them thousands of times in his economic discourses. But just as “eight-leaved clovers” had been mistaken for “workers,” audiences would hear different things, make wildly different judgments about their meaning and effects, and in the end polarize the choices between capitalism and communism, missing the collective context and dreams that had brought these words to consciousness in the first place.

Main Sources

The Worldly Philosophers, by Robert L. Heilbroner

The Communist Manifesto, by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Grand Pursuit, by Sylvia Nasar

Next Week: The Calculus of Capitalism

What Marx provided was a theoretical blueprint for cracks that lay in the foundation of a new economic edifice called capitalism. And he did it in the way many intuitive but slightly skewed geniuses operate: by masking it in endless obsessive formulations that make one cry uncle and then demanding that no one deviate from its precepts. Clever…

by Alan Briskin | Collaboration, Collective Folly, Collective Wisdom, Conflict, Conscious Capitalism, Consciousness, Politics

A serial journal of cogent reflections and irreverent insights on the social effects of capitalism and the roots of partisan politics. Pairing prose with HDR photography and “flash points” drawn from current and historical perspectives, the author seeks to recover lost wisdom and courageous action beyond the shouting and noise of today’s headlines.

Chapter Sixteen

The Dark Prophet

Part II: Capitalism’s Shadow

Time Range: 1867-1883, 2012

It is easy to dismiss Marx as a revolutionist or even as a theorist of socialism, but much harder to ignore his warnings about capitalism. He had discovered the Achilles’ heel of economic arrangements that celebrated their ability to create prosperity, generate innovation, and provide a bounty of goods and services as well as jobs. Capitalism proclaimed itself the final act in the history of economic evolution. Marx refuted the claim. His diatribes, as painful and polarizing as they were, force us to become conscious of capitalism’s other consequences.

We are confronted with capitalism’s shadow, the dependence on jobs defined solely by the marketplace, the depletion of natural resources, and the addiction to material gratification and personal glory out of sync with spiritual, community, and personal growth.

Yet, for all these dark prophecies, they are still within the imagination to address. There is ample evidence of the power of human collaboration combined with science and social purpose to tackle even the most difficult social issues. The darkest prophecy that Marx left us was not about economic concentration, ecological destruction, or the effects of inequality. It was about ourselves. It was about human polarization, the nature of privilege, and feelings of revenge – things Marx understood deeply in his bones.

HDR (High Dynamic Range) Photography by Alan Briskin: multiple shots at different exposures are combined into one image in order to show “more of what’s there”.

His prophecy of successive business crises, continual warfare between nations, depletion of the earth’s resources, and mounting cynicism among the middle and lower classes was all predicated on the belief that government would do nothing about it. He believed that government would be a protector of the dominant classes — even as the dominant classes battled each other — or at best impotent, paralyzed to do anything significant about the crises that would unfold in waves.

Government officials railed Marx, in tones similar to a tormented Dr. Seuss, could not, would not stand up to the monied interests that supported their rise to political power and punished these same politicians if they deviated too sharply from the social narrative of economic growth. And that narrative was synonymous, questionable as it was, with progress, social good, and most critically the belief that money should never lie fallow but grow through investment, resulting in individual wealth accumulation. The hero’s journey, in capitalist mythology, overcame hardship in order to gain material wealth. And in gaining wealth gained wisdom and character. If only it was true.

Marx, often unkind, jealous, suspicious, even wrathful, staked his entire claim on the inability of individuals and social groups to see the predicament they were in. There could be no genuine conversation about altering the rules of capitalism in any significant way. Was he correct?

There is a final irony in all this. Capitalists and workers alike would follow the psychological script Marx laid out while believing they opposed his ideas. As groups on the right and left organized to battle the perceived dangerous actions of the other, they were fulfilling Marx’s prophecy. As unions became more organized, aggressive, and even violent in the early 20th century, they were following exactly Marx’s claim that capitalism would spawn its own detractors as workers learned to leverage their power. As certain capitalists fought against living wages for workers, initiated offshore production to increase their surplus value, and battled regulations for protecting the safety of workers as well as the environment, they were fulfilling Marx’s interpretation of how a ruling class would operate. As governments swung from welfare programs to austerity policies, their basic incompetence or incapacity to act was revealed.

Marx’s assumption was that individuals were not free to think beyond the shackles of their immediate self-interest. Given the structure of profit making, Marx asserted that individuals would choose to maximize their gain at the expense of others, regardless of the consequences. This makes nearly everyone operating within the capitalist system Marxist — at least in behavior. If there was an exception to his declaration about the lack of human agency, it was himself. Confounding his followers, he declared a few years before his death, “I am not a Marxist.”